Why Do Mosquito Bites Itch?

Authors: Cassandra Brand & Sam Marchetti

Imagine… a peaceful weekend getaway in the great outdoors; the smell of campfire in the air, stars twinkling above, and a faint yet persistent buzz in your ear. A dreaded buzz that you know will be followed by hours of itching. It's funny how something as small as a mosquito bite can be so annoying, but have you ever wondered why?

For the most part, mosquitoes feed on nectar from flowers.1 So, why do they attack us if we’re not flowers? Well, in order to reproduce, female mosquitoes need protein - something they can’t get from flower nectar. Fortunately for female mosquitoes (and unfortunately for us), human blood is an excellent source of protein! The mosquitoes are attracted to odours that humans release, which are a combination of carbon dioxide, lactic acid, and other compounds. Our DNA determines how this odour is slightly different from person to person, which leads to mosquitoes being more attracted to some people than others.2 Mosquitoes also might be more attracted to people who are pregnant, infected with malaria, or eat specific foods like bananas or drink beer.3

However, our bodies don’t give up blood without a fight. We have several defense mechanisms in place to keep us healthy. The skin is our physical barrier, which provides our first line of defense from infection. If the skin is broken through as a result of injuries, such as cuts or bites, our blood cells will clot and seal the wound to prevent excess blood loss. We also have an immune system, a complex network of cells and molecules in the body that serve to attack particles from outside sources (these particles are known as antigens). While extremely helpful, these defense mechanisms are not completely foolproof.

After landing, female mosquitos break the first line of defense, by probing our skin with a straw-like mouthpiece in search of a blood source beneath the skin to feast on.4 During this process, the mosquito deposits small amounts of saliva into our skin.5 This saliva contains many antigens, some of which are large molecules that override our body’s cellular defense mechanisms and make more blood flow to the area instead of clotting and stopping.6 As a result, our blood vessels expand, increasing the amount of blood flowing past the mosquito’s mouthpiece, into the mosquito’s mouth.7 With both our physical and cellular defenses bypassed by the clever mosquito, this leaves it up to our immune system to protect us. Antigens in the mosquito’s saliva are recognized by our immune system and signal for our immune response to take action.8

Sound straightforward so far? It is! The next part is a bit more complicated though so bear with me here.

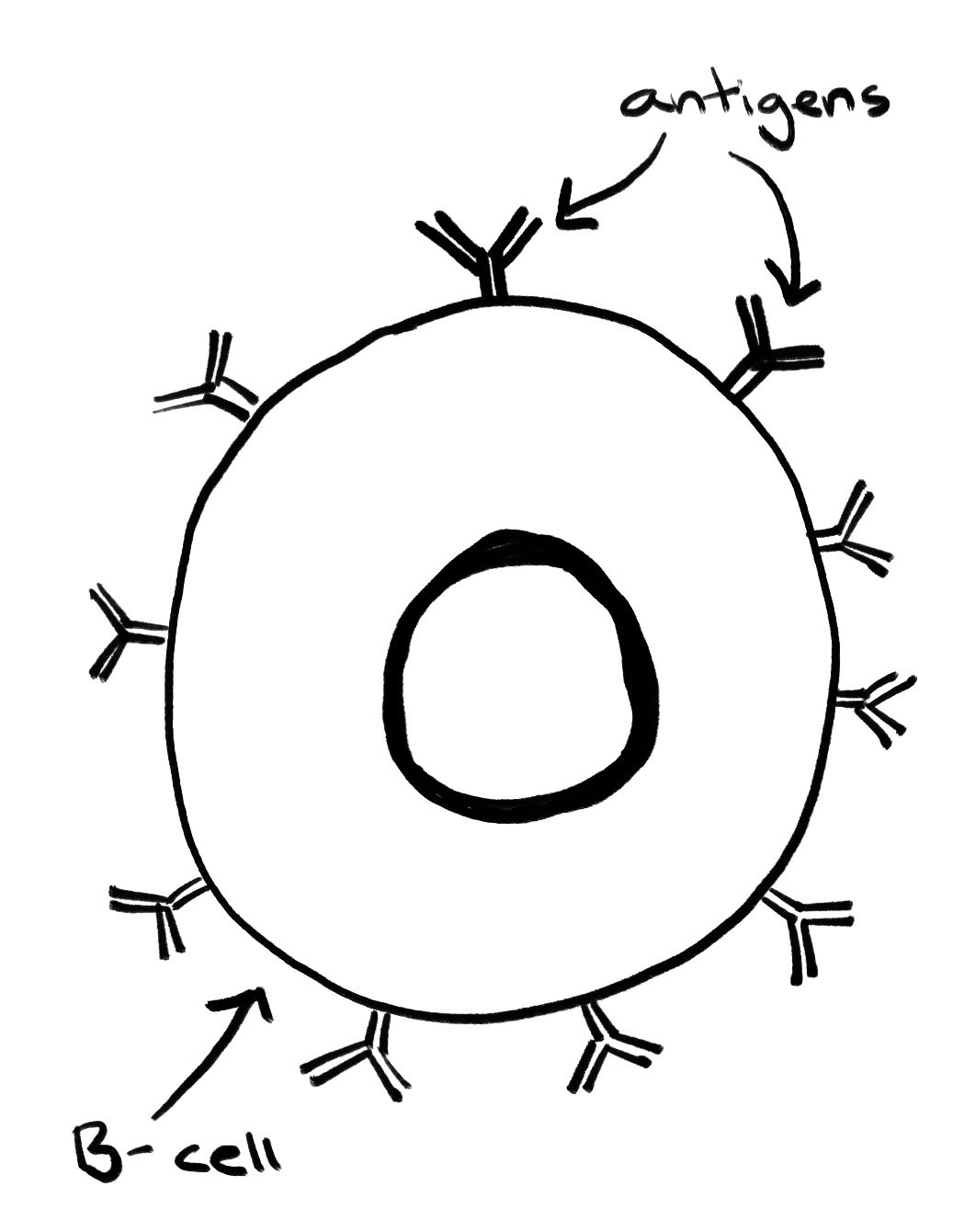

Our immune system is composed of two main divisions: innate and adaptive immunity. Innate immunity are sort of general processes that always occur to fight any infection, and adaptive immunity are more specific actions that our immune system takes to fight specific infections once the infection is recognized. When our skin and cellular responses fail, and antigens are introduced into our blood, some immune cells (called non-specific immune cells) respond by attacking the antigens. This is our first line of innate immunity, and these cells produce what we call “cellular messengers” – molecules that signal to amplify the immune response.9 While this is happening, other innate immune cells are bringing some of the antigens to some of our adaptive immune cells (called B and T cells).10 These adaptive immune cells recognize the antigens from the mosquito and produce antibodies–molecules which help mark antigens for the body to remember later on. This memory is important to our immune system so that next time you get bitten, it can respond faster.

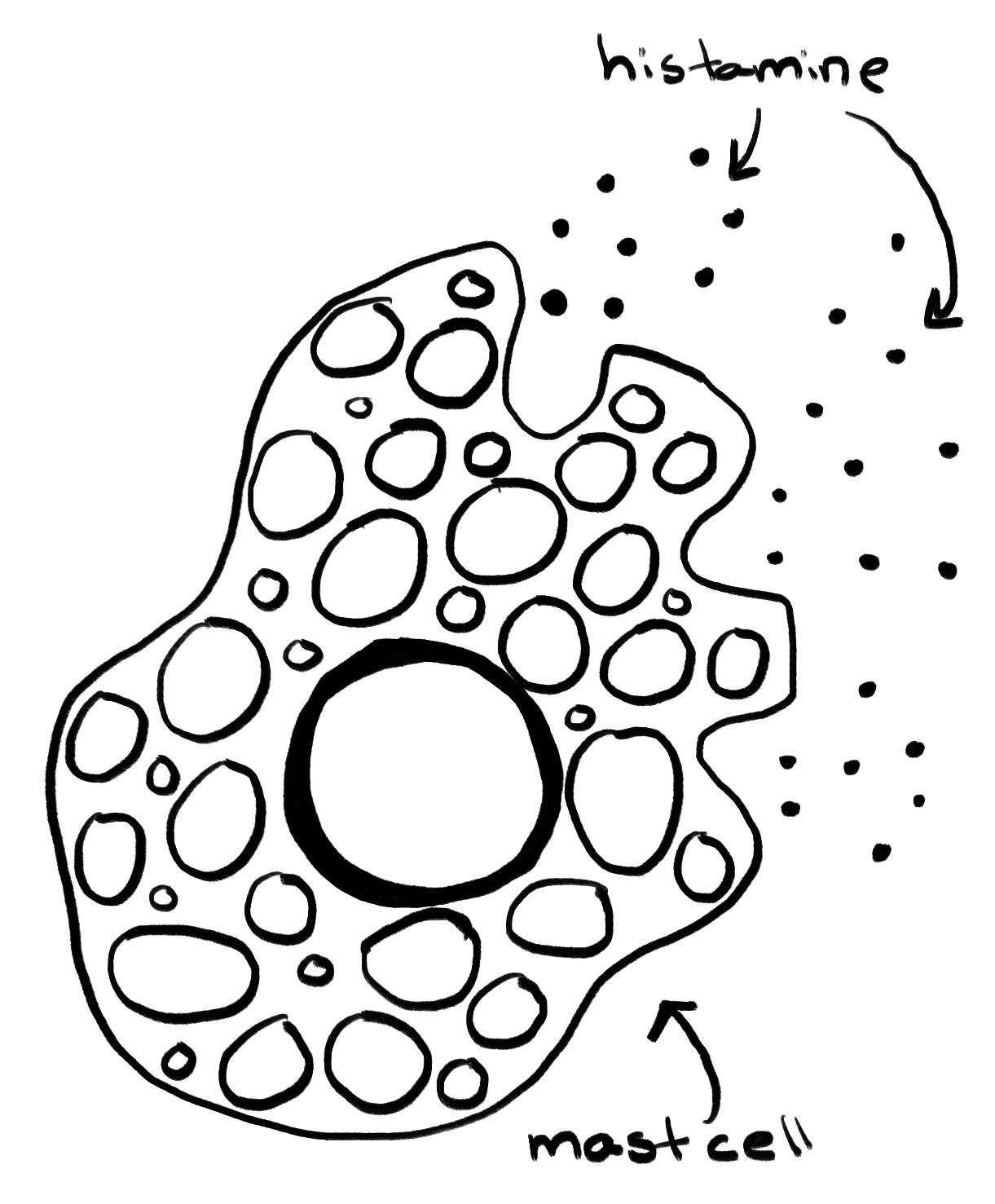

Both the innate and adaptive immunity divisions are active during the immune response towards mosquito saliva, but one molecule released in this response is particularly important in generating that irritating itch, histamine. Histamine is released by innate immune cells, and makes it easier for cells or small substances to pass through the walls of your capillaries, veins, and arteries (which all carry blood).11 This means more immune cells can be transported faster to the site of the bite (which is also why the area around the bite swells).12 The adaptive immune system can also trigger histamine release, and mosquito saliva itself has been reported to contain traces of histamine.13,14 As histamine builds up at the site of the bug bite from these different sources, the small molecule binds to receptors on nerve fibers in the skin, causing that itch we are all too familiar with!15

Whew! That was a bit difficult to explain but hopefully you followed along. Basically a female mosquito stings us (and sucks up our blood), and our body produces a molecule to stop the blood from leaving. But a side effect of the molecule is that we end up with an itch. Lucky for us, we do know that pain can block histamine related itches, meaning that simple at-home remedies like applying heat or baking soda can give us some relief!16 So next time you’re out camping, remember that that terrible itch is just a sign that your immune system is taking great care of you and is nothing your body can’t handle.

Klowden, Marc J. 1995. “Blood, Sex, and the Mosquito.” BioScience, no. 45 (5): 326–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/1312493.

Pingen, Marieke, Michael A. Schmid, Eva Harris, and Clive S. McKimmie. 2017. “Mosquito Biting Modulates Skin Response to Virus Infection.” Trends in Parasitology, no. 33 (8): 645–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2017.04.003.

Pingen, “Skin Response”.

Pingen, “Skin Response”.

Vander Does, Ashley, Angelina Labib, and Gil Yosipovitch. 2022. “Update on Mosquito Bite Reaction: Itch and Hypersensitivity, Pathophysiology, Prevention, and Treatment.” Frontiers in Immunology, no. 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1024559.

Pingen, “Skin Response”.

Pingen, “Skin Response”.

Vogt, Megan B., Anismrita Lahon, Ravi P. Arya, Alexander R. Kneubehl, Jennifer L. Spencer Clinton, Silke Paust, and Rebecca Rico-Hesse. 2018. “Mosquito Saliva Alone Has Profound Effects on the Human Immune System.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, no. 12 (5): e0006439–e0006439. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006439.

Vogt, “Mosquito Saliva”.

Vogt, “Mosquito Saliva”.

Vogt, “Mosquito Saliva”.

Pingen, “Skin Response”.

Fostini, Anna C., Rachel S. Golpanian, Jordan D. Rosen, Rui-De Xue, and Gil Yosipovitch. 2019. “Beat the Bite: Pathophysiology and Management of Itch in Mosquito Bites.” Itch, no. 4 (1): e19–e19. https://doi.org/10.1097/itx.0000000000000019.

Shim, Won-Sik, and Uhtaek Oh. 2008. “Histamine-Induced Itch and Its Relationship with Pain.” Molecular Pain, no. 4 (July): 29–29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-4-29.

Shim, “Histamine-Induced Itch”.

Shim, “Histamine-Induced Itch”.